The following are my (Graham Coop, @graham_coop) brief thoughts on Sriram Sankararaman et al.’s arXived article: “The date of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans.”. You can read the authors’ guest post here, along with comments by Sriram and others.

Overall it’s a great article, so I thought I’d spend sometime talking about the interpretation of the results. Please feel free to comment, our main reason for doing these posts is to facilitate early discussion of preprints.

The authors analysis relies on measuring the correlation along the genome between alleles that may have been inherited from the putative admixture event [so called admixture. The idea being that if there was in fact no admixture and these alleles have just been inherited from the common ancestral population (>300kya) then these correlations should be very weak, as there has been plenty of time for recombination to break down the correlation between these markers. If there has been a single admixture event, the rate at which the correlation decays with the genetic distance between the markers is proportional to this admixture time [i.e. slower decay for a more recent event, as there is less time for recombination]. These ideas for testing for admixture have been around in the literature for sometime [e.g. Machado et al], its the application and genome-wide application that is novel.

As you can tell from the title and abstract of the paper, the authors find pretty robust evidence that this curve is decaying slower than we’d expect if there had been no gene flow, and estimate this “admixture time” to be 37k-86k years ago. However, as the authors are careful to note in their discussion, this is not a definitive answer to whether modern humans and Neandertals interbred, nor is this number a definite time of admixture. Obviously the biological implications of the admixture result will get a lot of discussion, so I thought I’d instead spend a moment on these caveats. [This post has run long, so I’ll only get to the 1st point in this post and perhaps return to write another post on this later].

Okay so did Neandertals actually mate with humans?

The difficulty [as briefly discussed by the authors] is that we cannot know for sure from this analysis that the time estimated is the time of gene flow from Neandertals, and not some [now extinct] population that is somewhat closer to Neandertals than any modern humans.

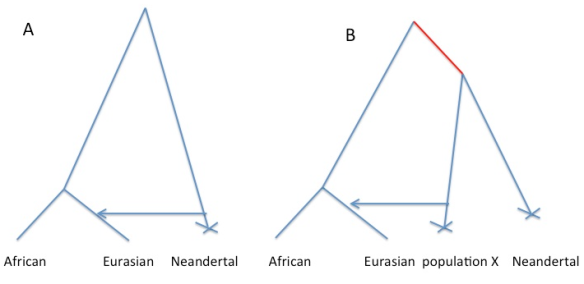

Consider the figure below. We would like to say that the cartoon history on the left is true, where gene flow has happened directly from Neandertals into some subset of humans. The difficulty is that the same decay curve could be generated by the scenario on the right, where gene flow has occurred from some other population that shares more of its population history with Neandertals than any current day human population does.

Why is this? Well allele frequency change that occurred in the red branch [e.g. due to genetic drift] means that the frequencies in population X and Neandertals are correlated. This means that when we ask questions about correlations along the genome between alleles shared between Neanderthals and humans, we are also asking questions about correlations along the genome between population X and modern humans. So under scenario B I think the rate of decay of the correlation calculated in the paper is a function only of the admixture time of population X with Europeans, and so there may have been no direct admixture from Neandertals into Eurasians*.

First thing is first, that doesn’t diminish how interesting the result is. If interpretation of the decay as a signal of admixture is correct, then it still means that Eurasians interbred with some ancient human population, which was closer to Neandertals than other modern humans. That seems pretty awesome, regardless of whether that population is Neanderthals or some yet undetermined group.

At this point you are likely saying: well we know that Neandertals existed as a [somewhat] separate population/species who are these population X you keep talking about and where are their remains? Population X could easily be a subset of what we call Neandertals, in which case you’ve been reading this all for no reason [if you only want to know if we interbred with Neandertals]. However, my view is that in the next decade of ancient human population history things are going to get really interesting. We have already seen this from the Denisovian papers [1,2], and the work of ancient admixture in Africa (e.g. Hammer et al. 2011, Lachance et al. 2012). We will likely discover a bunch of cryptic somewhat distinct ancient populations, that we’ve previously [rightly] grouped into a relatively small number of labels based on their morphology and timing in the fossil record. We are not going to have names for many of these groups, but with large amounts of genomic data [ancient and modern] we are going to find all sorts of population structure. The question then becomes not an issue of naming these populations, but understanding the divergence and population genetic relationship among them.

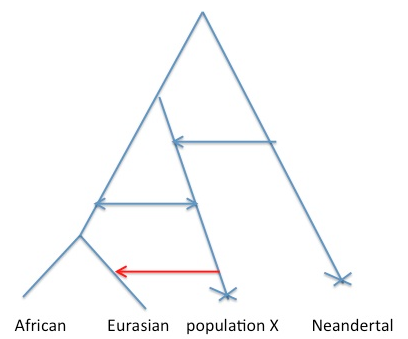

There’s a huge range of (likely more plausible) scenarios that are hybrids between A and B that I think would still give the same difficulties with interpretations. For example, ongoing low levels of gene flow from population X into the Ancestral “population” of modern humans, consistent with us calling population X modern humans [see Figure below, **]. But all of the scenarios likely involve some thing pretty interesting happening in the past 100,000 years, with some form of contact between Eurasians and a somewhat diverged population.

As I say, the authors to their credit take the time in the discussion to point out this caveat. I thought some clarification of why this is the case would be helpful. The tools to address this problem more thoroughly are under development by some of the authors on this paper [Patterson et al 2012] and others [Lawson et al.]. So these tools along with more sequencing of ancient remains will help clarify all of this. It is an exciting time for human population genomics!

* I think I’m right in saying that the intercept of the curve with zero is the only thing that changes between Fig 1A and Fig 1B.

** Note that in the case shown in Figure 2, I think Sriram et al are mostly dating the red arrow, not any of the earlier arrows. This is because they condition their subset of alleles to represent introgression into European and to be at low frequency in Africa. We would likely not be able to date the deeper admixture arrow into the ancestor on Eurasian/Africa using the authors approach, as [I think] it relies on having a relatively non-admixed population to use as a control.

Pingback: Most viewed on Haldane’s Sieve: August-September 2012 | Haldane's Sieve

Pingback: Haldane’s Sieve sifts through 2012 | Haldane's Sieve

Thanks for the comments Graham, it’s really interesting.

I used to work closely on these issues (a while back now) and, with my now somewhat distant point of view, I can’t help feeling like there is something fundamentally difficult (almost hopeless?) about making firm claims, as you very well point out. These trees that you draw are only meaningful if the definition of population is meaningful. We like to give names, “Neanderthal” for example, and bin individuals in discrete populations when one is really dealing with a continuous process. It’s not that statements cannot be made, but with so many years back, the resolution is bound to be limited. As a consequence there is an unavoidable component of story telling which I tend to feel uncomfortable about. I think this is what drove me toward more medical genetics questions, because these are inherently more reproducible than evolutionary ones.

This being said, one still need to try to understand that process. Good to see that you are optimistic about the future of population genetics, and I suspect I am overly pessimistic about this.

I’ve made a copy of this at figureshare: http://figshare.com/articles/Blog_post_on_Sankararaman_et_al_The_date_of_interbreeding_between_Neandertals_and_modern_humans_/832539